Chondrites

- Introduction

- Comets

- Asteroids

- Meteorites

- Meteor Showers

- Rock Types

- Identification

- Origins

- Destruction

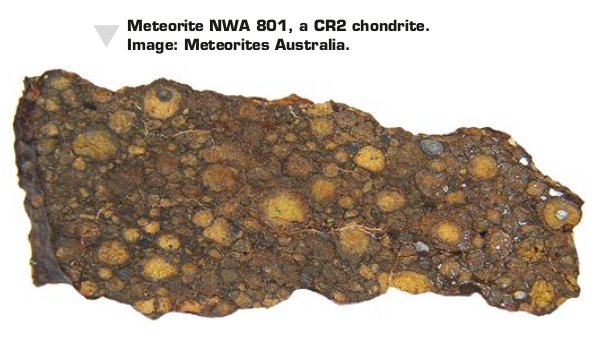

By far and away the most common type of meteorite is the chondrite – they number 27,000 out of the 38,000 discovered rocks from space. They’re notable for their brilliantly coloured spherical crystals called chondrules, which are filled with all kinds of minerals such as olivine, pyroxene, iron and silicon. They are finished off with flecks of iron-nickel and sometimes calcium and aluminium too (the iron makes them slightly magnetic). Chondrites are thought to have formed at the same time as the inner planets, and preserve dust from the primordial protoplanetary disc that has been flash-heated to 1,000°C. Evidence of this is seen in the ‘refractory inclusions’ present in chondrites (refractory materials are elements that have condensed at high temperature but maintained their physical and chemical structure). The cause of this flash-heating is one of the many mysteries of the environment in which the planets formed; perhaps they were caught up in shock waves rippling through the disc, or got too close to the Sun, or were the victims of the constant onslaught of impacts as embryonic planets – planetesimals – smashed into one another.

Chondrites come in four divisions: ordinary, carbonaceous, enstatite and rumuruti. The latter two are quite simple; enstatite meteorites are oxygen poor, lack metals and number about 200 finds, whilst 900 rumuruti meteorites have been discovered, with a higher ratio of oxygen-17 to oxygen-16 than in Earth rocks, and totally devoid of any metals. Ordinary chondrites (which make up 90 percent of all chondrites) and carbonaceous chondrites are far more complex.